Branding?

Mapping a term: origin, meaning and interpretation.

Some time ago, John Rushworth, a partner at Pentagram London, wrote the foreword to the publication Brand Identity Now: 'Branding has grown to be more than visual identity’. He then goes on to describe a classic identity process, albeit somewhat superficially. A more recent article, 'Ein enormes Potenzial von Marken bleibt ungenutzt' (The enormous potential of brands remains untapped), is by Simone Wies and Marc Fischer, who both teach marketing [2]. In it, they use Harley-Davidson as an example to illustrate how the company could utilize its brand more effectively. It is immediately apparent that the description refers to aspects of corporate strategy that are clearly unrelated to brand management. We will not discuss this article in depth here but will simply note that the term 'branding' is used very imprecisely — once again, we are dealing with a buzzword that is often used without reflection. The topic of 'branding' is often considered part of marketing. However, the question of identity and branding has a completely different origin, which most experts are unaware of.

The development of the theory of image, identity and branding

In German-speaking countries, the term 'Erscheinungsbild' (appearance) was originally used. Three pioneering projects were implemented long before the terms’ 'identity' and 'branding' came into use: AEG, Olivetti and, later, IBM. Peter Behrens (1868–1940) [3]., who was also a co-founder of the German Werkbund, began planning and implementing AEG's corporate identity in 1907. This created a prototype for the image of large companies. He created a model for an integrated corporate identity ranging from business cards to architecture. The brilliant designer Wilhelm Deffke (1887–1950) made a significant contribution to this project, shaping the visual appearance of AEG considerably.

The Italian company Olivetti represents another milestone. In the 1930s, the company's visionary entrepreneur, Adriano Olivetti (1901–1969), began to cultivate his company's image systematically [3]. To this end, he hired renowned designers such as Giovanni Pintori (1912–1999), Marcello Nizzoli (1908–1958), Ettore Sottsass (1917–2007) and Mario Bellini (born 1935). Olivetti recognized that the company's presentation and communication should encompass not only its image, but also its social and cultural components. He was thus a pioneer of what would later become known as corporate culture.

Thomas J. Watson Jr. (1914–1993) added an additional component to the topic of image with IBM [5]. He expanded the concept, considering the quality of appearance to be a competitive advantage. Watson collaborated with Paul Rand (1914–1996), Eliot Noyes (1910–1977) and, later, Josef Müller-Brockmann (1914–1996). Together, they shaped IBM's design, contributing to the company's brand-building efforts through their technological leadership. Their work set the standard for quality in the field of visual identity.

The designers Walter Landor (born Walter Landauer, 1913–1995) and Frederik Henri Kay Henrion (born Friedrich Heinrich Karl Henrion, 1914–1990) met in Paris after emigrating to France. Together with Jean Colin (1912–1984 [6]) they developed the first theoretical concepts on the impact and function of images, known as the 'Théorie de l'image'. They discussed how visual communication could define not only products and services, but also entire organizations. This formed the basis of the concept of 'corporate image'. Landor further developed these theories at his renowned agency, Landor & Associates, in Los Angeles [7], and achieved great success in implementing them. In turn, FHK Henrion implemented complex design programs for British Leyland, BEA (British European Airways) and KLM in London, and together with Alan Parkins wrote the first comprehensive theory in the publication Design Coordination and Corporate Image [8]. Through their ideas, concepts and successful projects, Landor and Henrion laid the foundations for image theory and its commercial implementation.

An important contribution was made by James K. Fogleman, the American designer and manager of CIBA USA (a pharmaceutical company now known as Novartis). At an international CIBA managers' conference in 1953, he presented a highly professional and systematic approach to corporate identity [9] designed to reflect the specific culture of a science-based corporation coherently. During his presentation, he discussed the concept of 'integrated design', or 'a controlled visual representation of the corporate personality', and 'a sense of unity, clarity, or singleness of viewpoint'. He also argued that 'policies are necessary which, over time, will tie together to form a unified corporate expression of the company's character and personality' [10]. By shifting the focus from identification (logos) to systems, he made a significant contribution to the theory of corporate identity. He later brought these ideas and concepts to Unimark International, the agency he co-founded. Through this agency, the idea of corporate image spread throughout the USA.

Another influential figure is David Ogilvy (1911–1999), an Englishman who brought the perspective of advertising to the identity discussion. According to his definition, 'the image of a brand is a complex symbol. It is the sum of all impressions that the consumer receives from many sources”. By asking questions such as “What do people feel and think when they think of this brand?”, he introduced the psychological-communicative dimension to the theoretical discourse. He published his ideas in his late book, Ogilvy on Advertising: I Hate Rules [11].

Wally Olins (Wolf Olins) is a leading practitioner, strategist and theorist of the concept of corporate identity. He popularized and systematized the concept of corporate identity in the business world more than anyone else. He expanded upon it by introducing the three pillars of corporate behavior, communication and design, which remain relevant today. As early as 1978, he published The Corporate Personality, in which he addressed the psychological aspects of identity. In the short book The Wolff Olins Guide to Corporate Identity, published in 1984 [12], he summarized all theories on image and identity, presenting them as a coherent, systematic whole. He organized the subject of identity into the aforementioned areas of behavior, communication and appearance; addressed target groups, business ideas and various brand models (monolithic, endorsed and branded); and formulated practical procedures to enable clients to implement an identity process. Olins took the concepts discussed by Landor and Henrion in Paris, which had been implemented by companies such as AEG, Olivetti, and IBM either intuitively or strategically, and turned them into a clear, communicable, and marketable discipline. In essence, he invented identity consulting. The final page of the Wolff Olins publication concludes: 'A corporate identity program is a complex, subtle instrument, needing constant care and attention. It changes and moves with the organization. It provides a constant reminder to both insiders and outsiders about the organization's achievements and aspirations. It is the essential glue that holds companies together.'

From the author's perspective, these are the fundamental principles that underpin the concepts of identity and branding. However, there are certainly other notable contributions, such as the work of K. Birkigt, M. M. Stadler and H. J. Funk, entitled Corporate Identity: Fundamentals, Functions, Case Studies [13], and the work of Peter G. C. Lux, who introduced the concept of personality traits. Another notable contribution is the work of Roman Antonoff, who popularized the idea of corporate identity management in Germany with his CI Report [14].

Developments since the millennium

Having described the pioneering era and introduced its protagonists, the question naturally arises as to who the key drivers of the new phase from the 1990s onwards are. Below are a few highlights from the flood of publications collected by the author through his network.

In Here Comes Everybody [15], Clay Shirky vividly explains how the internet is undermining traditional production and communication hierarchies, introducing the concept of 'co-creation'. In The New Rules of Marketing and PR [16], David Meerman Scott argues that the old rules of one-way broadcasting are obsolete and must be replaced by authentic, direct dialogue with target groups. Two of the most influential books of the last 20 years are The Brand Gap and ZAG [17] by Marty Neumeier. Neumeier calls for the interplay of strategy and creativity. In ZAG, he argues that, in a world characterized by an oversupply of information, brands must be radically different in order to be noticed. He believes that traditional differentiation is no longer enough. Today, companies need 'radical differentiation' to create lasting value for their customers, employees and shareholders. This publication explains, among other things, how customer feedback on new products and messages can be 'read'. It also outlines the 17 steps to creating 'difference' in a brand and demonstrates how a brand's 'uniqueness' can be transformed into 'authenticity'. B. Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore initiated the transition to an experience economy very early on with their work The Experience Economy [18]. They also lay the groundwork for the idea that a brand must offer an unforgettable, staged experience. Simon Sinek popularized this concept in an unconventional way with Start with Why [19] and his “Golden Circle” (Why, How, What). 'Why' is no longer just a theoretical concept, but a central management and branding tool. 'People don't buy what you do; they buy why you do it' – this is how he summarizes his idea. In 'Change by Design', Tim Brown, CEO of IDEO [20], further developed the concept of the designer as a strategic problem solver who develops entire brand experiences, rather than just a creator. Another important publication is Creative Intelligence: Harnessing the Power to Create, Connect, and Inspire, in which Bruce Nussbaum summarizes his ideas. He defines creativity as the new central economic competence and explains how it can be learned and scaled up. 'Unstuck: A Tool for Yourself, Your Team, and Your World by Keith Yamashita and Sandra Spataro [22] is not a theoretical treatise but a practical guide and 'toolbox' that explains the methodology of Stone Yamashita. The authors apply the approach used by large companies such as Apple to individuals, teams and organizations. They offer a series of models, questions and frameworks ('The 7 Energies', 'The 29 Flaws') to analyze and resolve situations where progress is stalled. The connection to identity work is established through topics crucial to a modern brand identity, such as clarity of goals ('why are we here?'), positive culture and energy ('what is the mood in our team?'), constructive strategy and implementation ('how do we get from thinking to doing?'), and behavior and change ('what guides us and how do we break with [...]?').

The contributions of the pioneers and new ideas

We recognize that a cycle ended in the 1990s and a new one began. This development can be summarized as follows: The concepts of Henrion, Landor & Co. were the answer to the age of mass production and mass communication, also known as the broadcast era. Next came the response to the digital revolution, globalization and the fundamental shift in power from companies to consumers. You could say that the pioneers taught us how a brand speaks. The new developments, on the other hand, are teaching us how a brand listens to and behaves within an ecosystem. We are also seeing that sustainability, social responsibility and ethical issues are becoming ever more relevant in the commercial sphere. A brand's identity is increasingly defined by its contribution to society and its role in solving global problems (ESG is the keyword here). This is no longer a 'nice-to-have' but a central component of identity.

In summary, the pioneers established the basic building blocks of brand identity, including the logo, visual identity, corporate philosophy, corporate culture and consistent communication. At Olins, these are referred to as 'everything a company says, makes, and does'. This answers the question of what components make up a corporate identity. Their successors in the post-1990s era refined these concepts, defining how these building blocks work, interact and are experienced in a complex digital landscape. They address questions such as: How does a brand behave in real time on social media? How can values be conveyed through an app or demonstrated in a supply chain? Building on the theories of the pioneers, they expand them with new perspectives, making them fit for the future.

Where do we stand today?

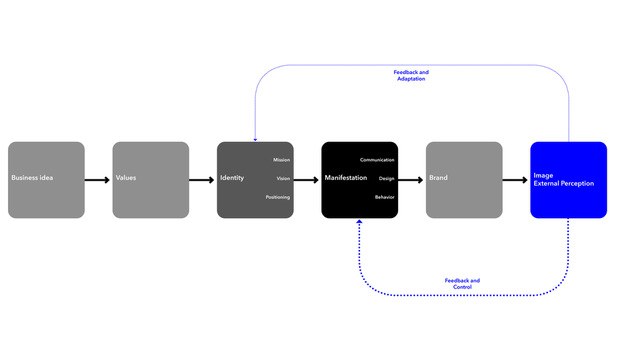

Examining the evolution of terminology, it is evident that the emphasis has transitioned from 'image' to 'identity' and finally to 'branding'. With 'image', the focus was on impact, whereas with 'identity', it was on the essence of the content. With 'branding', the focus is on the brand as a label and signature. Asking ourselves what fundamental changes or improvements have taken place reveals that little has changed in terms of the fundamentals, although much has evolved in terms of the details, particularly implementation. Let's now look at these basic terms and try to piece together the overall concept of identity and branding.

– Business idea: The origin and the 'why' factor. The unchanging foundation.

– Values: The moral and ethical rules of the business. They form the foundation that guides our actions.

– Identity: the independent essence. It condenses the mission, vision and positioning into a concise self-image.

– Manifestation: The visible and tangible reality of behavior, communication and design.

– Brand: The perceived promise that arises from consistent manifestation.

– Image: The subjective overall impression held by target groups.

Compared to the pioneering phase in which this framework was first developed, the world today is extremely dynamic. This is primarily due to the internet, digitalization and the enormous acceleration in the production of information. We can see that business ideas and values do not change unless the business itself undergoes fundamental change. Like the business idea, values should remain stable, while the plausibility of the identity must be periodically reviewed — this is a medium-term task. On the other hand, manifestation, i.e. communication, behavior and design, should be continuously monitored based on market feedback. Adjustments should be made as necessary. Any fundamental revision must be carefully considered, sensitively decided upon, and designed in connection with existing equity.

Concluding remarks:

The first and most important step in creating a meaningful identity program is to establish a set of shared values, as well as a sustainable mission and vision, both of which should be based on the business idea. It is important to note that everyone and every institution or company has an identity. The question is not whether this identity exists, but how to engage with it consciously.

Design can communicate beliefs, intentions and values in a comprehensible way. This is its strength. It concerns both content and form. Identity only becomes understandable through design and communication. However, communication always begins with a defined framework of content. When the relationship between an organization’s origins, current constitution and future direction is clearly defined and recognized, design becomes a powerful tool for presenting the company or institution in a sustainable way.

Companies are perceived by their economic partners through the individuals representing them, their behavior, and their products, services and communication. In today's economy, communication plays a strategic role. It's not just about media presence; it's also about the quality of the overall brand experience. This applies to personal contacts, products or services, and the stronger the digital presence, the stronger the analogue presence too. From these impressions, customers form their own subjective impression of the company and its offerings. The clearer and more distinct these impressions are, the more positive the perception and image will be.

The stringency of the content creates credibility, arouses interest, and creates lasting significance. The design guarantees recognition. The result is a strong image, an independent reputation and an unmistakable profile — all of which are essential prerequisites in today's economy.

“Identity manifests itself in the way we think, speak, move, and dress, in our tone of voice, and in the way we smile.” And this also applies to companies and institutions, because they too can “smile” – through their customer service, their product design, and their overall charisma [23] .

[1] Wiedemann, Julius: 2009, Brand Identity now; Taschen, Köln

[2] Wies, Simone und Fischer, Marc: 2025, Ein enormes Potential von Marken bleibt ungenutzt; Frankurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Frankfurt

[3] Behrens, Peter: 2015, Zeitloses und Zeitbewegtes; Dölling und Galitz Verlag, München, Hamburg

[4] Archivi Olivetti, https://www.archiviostoricolivetti.it/en/olivetti-digital-museum/

[5] IBM Heritage, IBM Design, https://www.ibm.com/history/design-program

[6] Colin, Jean presumably a Swiss typographer who worked in Paris at Deberney & Peignot (biographical data not available)

[7] Thackray, Nicholas: Walter Landor, https://www.phable.io/top-branding-agencies/walter-landor-the-visionary-who-revolutionized-modern-branding

[8] Henrion, Frederik Henri Kay and Parkin, Alan: 1967, Design coordination and corporate image; Studio Vista, London / Reinhold Publishing Corporation, New York

[9] Fogleman, James K. was a US designer who headed the communications department at CIBA-USA and later co-founded Unimark International (biographical data not available)

[10] Meggs, Philip B.: 1963, A History of Graphic Design, Seite 384, 385; Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York

[11] Oglivy, David: 1983, Ogilvy on Advertising, Crown Publisher Inc., New York

[12] Olins, Wally: 1984, The Wolff Olins Guide to Corporate Identity; published by Wolff Olins, London

[13] Birkigt, Klaus, Stadler , Marinus und Funck, Hans Joachim: 1980 (continuously updated), Corporate Identity. Grundlagen Funktionen Fallbeispiele; Verlag Moderne Industrie, Landsberg/Lech

[14] Antonoff, Roman: 1985 (presumably further editions have been published), CI-Report; Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Frankfurt

[15] Shirky, Clay: 2008, Here Comes Everybody; Penguin Press, London

[16] Scott, David Meerman: 2007 (continuously updated), The New Rules of Marketing and PR

[17] Neumeier, Marty: 2005, The Brand Gap and 2007, ZAG; AIGA New Riders, New York

[18] Pine II, B. Joseph and Gilmore, James H.: 2011, The Experience Economy – past, present, future; Harvard Business Press, Boston

[19] Sinek, Simon: 2009, Start with Why; Penguin Press, London

[20] Brown, Tim: 2009, Change by Design; Harper Collins Publishers, New York

[21] Nussbaum, Bruce: 2013, Creative Intelligence: Harnessing the Power to Create, Connect, and Inspire; Harper Collins Publishers, New York

[22] Spataro, Sandra and Yamashita, Keith: 2007, Unstuck: A Tool for Yourself, Your Team, and Your World; Portfolio Publishers, New York

[23] Vetter, Peter and Leuenberger, Katharina: 2016, Design as Investment – Design and Communication as Management Tool; Spielbein Publishers, Wiesbaden

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the assistance of DeepSeek (DeepSeek Company, version 2025-01-17) in the preparation of this research. The model was used for brainstorming initial ideas, refining research questions, and proofreading early drafts. The final content, analysis, and conclusions are my own.