Brand Architecture: It’s not a naming exercise. It’s a growth system.

Why the way your brands connect, signal, and scale determines whether your portfolio accelerates or collapses under its own complexity.

(ORIGINALLY WRITTEN FOR MARCAS COM SAL)

Among the disciplines of branding, this is one that generates the most doubt and discussion, and I can share some reflections from my time at Microsoft, Google, and the tech industry.

But first, to establish a common starting point, I offer a definition of brand architecture: “The system by which an organization’s products or services connect and differentiate themselves from each other, using visual and verbal elements to indicate relationships and hierarchy.”

The Edges of the Map

In the vast universe of brands, having a clear “brand architecture” is like having a well-drawn map: of neighborhoods, streets, and even aisles in a market. After all, with increasingly demanding, overloaded, and distracted consumers, it becomes crucial for your company to know exactly how to signal its offerings and experiences to help your audiences navigate.

If you are a branding professional, marketing manager, or startup leader trying to organize your offering, at the very least you have heard of the house of brands and branded house models. These are the “edges” of the map. On one side, the classic example of Procter & Gamble (P&G), with brands like Pampers, Pantene, and Gillette. Each of them operates independently and with its own identities.

us.pg.com

On the other side, the example of Virgin, with brands like Virgin Music, Virgin Mobile and Virgin Hotels. All of them adopt the same brand identity and personality.

virgin.com/virgin-companies

I will never forget the metaphor used by my colleague Tim Hoppin, now Global Head of Brand and Creative at Amazon’s AWS, from the time when we were both at Microsoft in Redmond, USA. I took the liberty of borrowing his brilliant slides, giving him credit, of course. In addition to demonstrating the brand architecture models in a completely understandable way, with a good dose of humor, he also argued that the vast majority of his business unit’s products and features should have descriptive names.

Imagine your brand as a supermarket that your consumers need to understand to wayfind.

In the first image, we have a house of brands, where each category or aisle receives

a brand. They signal distinction and differentiation. In the last image, we have a branded house, where the most important brand is that of the supermarket on the outside (a choice already made by the consumer) and the signage facilitates connection and flow between the aisles.

Where the Map Gets Confusing

Not everything is either a house of brands or a branded house. For example, where would you place Apple, Amazon, Microsoft or Google? All of these companies have a bit of both models, sometimes leaning more toward one than the other. Market reality often presents us with hybrid models, where elements of both approaches coexist.

At Microsoft, we used to say that we had a branded house of brands. This is because brand architecture is a living being and, in fact, the company shapes it in real time, launch by launch, trying to move it toward a more desired and manageable model. Consider Apple, which follows the branded house (or “monolithic,” using another branding jargon) model, where almost everything is identified by the name “Apple”: Apple Watch, Apple Music, Apple Pay and more recently Apple Intelligence. The company seems to have definitively abandoned the iMac, iPhone, iCloud pattern, partly due to the proliferation of “i-imposters” who take advantage of the fact that the prefix is not protected intellectual property (who knows, if one day they launch a truly revolutionary cell phone— instead of the repetitive annual increments — they might call it Apple Phone?). And even so, it still has a portfolio that also includes non-Apple names like Siri, Safari and AirPods.

Compare this with Amazon’s model, also hybrid, but in this case more due to inheriting brands from acquisitions until it figures out what to do with them. I always think of Amazon as the Yamaha of modern times: almost everything fits under it. The Amazon brand functions as a strong umbrella, ensuring recognition and trust for a wide range of services and products, such as Amazon Prime, Amazon Music and Amazon Web Services (AWS). In fact, last year they took an important step in harmonizing hundreds of brands by launching a new identity and visual system for the portfolio. At the same time, the company maintains strong and independent brands from the companies it acquires, such as Whole Foods, acquired in 2017, which maintains its own identity and market positioning. Still, the Amazon Prime brand is very present in the aisles and gondolas of the market, and subscribers enjoy discounts and benefits.

koto.studio/work/amazon

Google is another case of these hybrids. Some of its most used and well-known products follow the branded house model — Google Maps, Google Photos, Google Drive — conferring value and clarity to the parent brand. If it were today, I’m sure they would have named Gmail Google Mail, but it became so famous that rebranding became difficult. Even so, from time to time the company falls into the temptation of giving “special” names to what it considers a revolutionary product. It took time, and many errors and attempts, for them to definitively decide that Gemini would be the brand for its family of AI solutions, including LLMs, assistants and more. Not long ago, they were talking about Bard, Duet, Google Assistant and others, all now demoted and buried. Personally, I think the decision creates brand confusion: I trigger and use Gemini but still say “Hey Google” (and not “Hey Gemini”?) on my cell phone and my mini speaker.

about.google

Alphabet was also emblematic. In 2015, it emerged as a holding company to house Google and its other “bets,” such as Waymo and DeepMind, allowing Google to “breathe” as a brand more focused on internet services, in addition to ensuring focus and agility for distinct leadership teams. A smart move, it must be said, to prevent the Google brand from becoming overextended or associated with riskier projects. (One day I will still write about the naming, which I consider one of the best of the last decade.)

Why This Is Relevant to Your Company

If, on the one hand, these hybrid models allow for flexibility and adaptation—leveraging the recognition and trust in the main brand in some areas, while preserving or building separate brands for offerings that may benefit from a unique positioning—they also generate complexity in management and the risk of dilution of the main brand.

A poorly thought-out brand architecture can generate confusion—at the very least for your team and your consumers. Not to mention other stakeholders such as partners and investors. Just like in the initial example of the article, imagine a supermarket where one aisle is called “Shampoos and Conditioners,” another “Premium Do,” another “Visu Glam,” and a fourth “RaveMax.” Jokes aside, this happens in the best companies, and customers end up thinking: “Where am I supposed to go?”

Here I am not defending the branded house model, but it is essential to have this map drawn a priori, and coherence is essential. Even without knowing what all the neighborhoods, towns, streets, and buildings will be, drawing up a master plan that shows how the areas of your map relate and what criteria determine the special areas—and which will deserve differentiated branding or naming—is essential for growing in an orderly manner.

Furthermore, a brand architecture minimizes the time spent in internal discussions full of subjectivity and personal taste and signals the size of the budget needed to build new offerings in the minds of your target audience.

Some Practical Tips

A cardinal sin is to transform the organizational chart into brand architecture, often motivated by territorialism or a lack of focus on customer motivations, who are not obliged to know your internal structure. In an era where reorgs are constant, brand architecture becomes a hostage and meaningless.

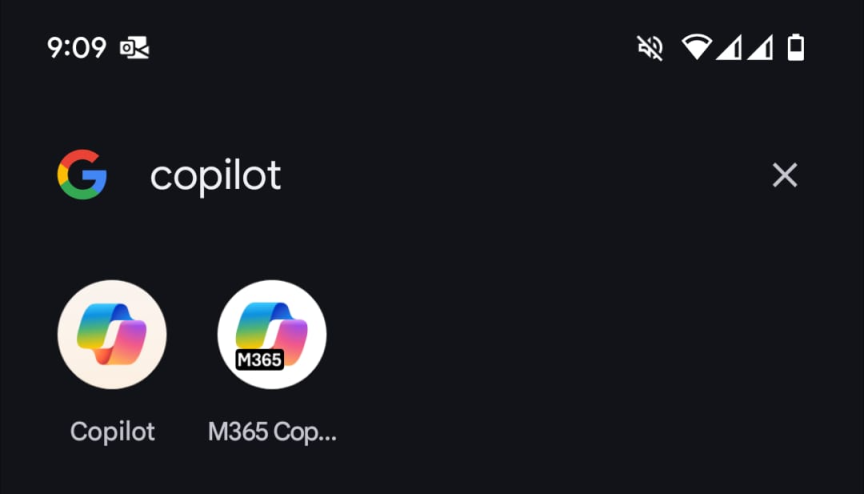

- For example, the Microsoft 365 icon on my cell phone, which gives access to my Word, Excel and PowerPoint files, recently changed to the Copilot icon, but written M365 Copilot (which has a tab written “Copilot”). The funny thing is that the “real” Copilot icon is right next to it. From my user perspective, I found it confusing. For me, it doesn’t matter that there is the “assistant” Copilot and the “integrated” Copilot, which I use within my documents, spreadsheets and presentations. It’s all Copilot. Don’t let the division of internal teams reflect in your branding

Thinking of brands as assets that need to be nurtured to grow, any brand beyond the minimum necessary represents inefficient spending. Thus, when designing a brand architecture, the most important question to ask—and investigate—is: what is the smallest number of brands needed for us to achieve our business objectives?

- For example, if a coffee company wants to build its position as a reference in the premium segment of national coffees, reaching 12% market share in the high end in the next 18 months, it should ask itself: what are the challenges and the effort required to enter this segment with an existing brand, or would we be more successful investing in a new brand?

When creating a new product or service, before thinking about a new brand, ask if it fits under an existing brand.

- For example, Microsoft’s Xbox was known for its console, as a hardware brand. Would its audience accept that the brand also represented gaming as streaming? Today Xbox Live and Xbox Game Pass seem like no-brainers, but at the time they may not have been

Don’t think about brand architecture in the abstract. Try to visualize them in the real world, in the places and touchpoints where they will actually appear. This helps you quickly see where the model works or breaks down.

- For example, ask your creatives or agency to apply the brand architecture to your website menu, to the buttons of mobile apps, to the SKU chooser of your service, to your social media channels, to the launch ad

My Final Message

In times of scarce resources and markets that move at lightning speed, a well-designed brand architecture is an essential tool for efficient and coherent decision-making in expanding businesses.

And for impatient and multitasking consumers, your brand needs to appear clearly. A brand decision should not be a costly, time-consuming and arduous task.

The sooner you face this puzzle, the faster you will feel the positive effects.

Incredible clarity. Even with years of experience in brand architecture, I found these examples and the strategic thinking behind them inspiring. Thanks for sharing!