About typography for non-typographers. And orientation for brand managers.

GOLDEN RULES (1)

Dealing with language - until the mid-seventies it was cast in lead.

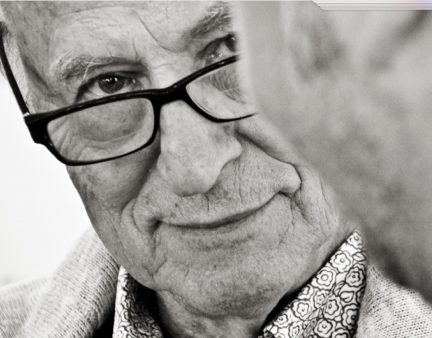

Experiences made by typesetter Olaf Leu from 1954 to 1957 in the manual typesetting shop of the Bauersche Giesserei in Frankfurt am Main.

"Masters don't fall from the sky. Talent helps, but without experience, commitment and the will to learn - over and over again - it doesn't work. I would have liked to have had the following text 15 years earlier and given it to my students to read."Prof. em. Stephan Müller, Leipzig University of Applied Sciences for Typography and Book Design.

1. How do you recognize the quality of a font?

This requires a practiced and, above all, trained eye. And you don't learn that at school. And nowadays - the year is 2025/26 - it certainly isn't. An alphabet consists of two sets of 26 letters. In addition, there are various "characters" such as commas, dots, brackets - square and round, and, and, and ... there are also numbers, 1 to 0. All of this is accommodated - or applied - in an emerging column and determines the typeface, the overall image.

There are fonts that have anomalies within their 26 individual letters, which makes the overall picture "restless". Look at the small "g", for example, it often looks like a twisted wire hanger - a coat hanger. An unmastered form! The same goes for the small "ß". Both "prevent" a harmonious overall picture. (One reason why I had equipped the COMPATIL with a "Fleischerhaken-g").

Harmony only arises when the individual letters fit together - and this changes with use. There are combinations that are "unfortunate" and cause difficulties right from the start. Letters like "v" and "w'", for example, which have a "light slant", have difficulty accommodating this slant with the next letter, balancing it out. For the whole thing is a play of darkness (the letter) and light (the open vistas). (In the Bauersche Gisserei there was a plane with which you could plane off the "lead shoulder" on the left or right - so you could influence "the incidence of light within a line").

2 How do you arrive at an assessment?

This is ultimately a matter of serious commitment to acquiring knowledge. There is no quick course here. You have to look at many things, compare them with each other and try them out. You can "read off" a lot, but ultimately it is the way you deal with things that you have acquired yourself and not read off. Because the latter is not "fixed", it's just an allure. In the past, there was an "apprenticeship" (3 years), then you were an "assistant", only then could you become a "master". Nowadays on the Mac, everything is faster, but it hasn't become more "masterful", rather the opposite.There has been a loss of the culture of harmonious typesetting.

3. Are there "scriptural recommendations"?

Yes, they do exist. And they are based on the masters. Zapf, Tschichold, G. G. Lange, Baum, Frutiger - all of them and other masters not mentioned here - have created harmonious works. Here the name of the master is an indication or guarantee of quality. Pay attention to names and then to what they have created. This is what I call the study of matter. And I can't and don't want to relieve anyone of the burden of study and the (considerable) time required for it. From little usually comes even less ...

4. Tips from the sewing box of the Bauer foundry:

Let's move on to a detail: a column.

The width of a column is individual. Let's assume a width of 9 to 10 cm - a recommended width, by the way, at which a reader can take in the whole line at a glance! (Already learned something, ha,ha ...) At the beginning there is an indent for the sake of better accessibility! How wide can it be? Here's a tip: Every alphabet used has two "thick" capital letters, namely the capital "M and the W". This "thickness", or volume, determines the indentation. And this depends on the width of the overall line. Take a minimum of three thick "M "s - a maximum of four! Then you have created the right harmonious indentation! (ei, ei, I didn't know that, nor did the professor, ha, ha ...)

And how do I do this with the word spacing? This is determined by the interior of the lowercase "u" or "n" - or, in the case of capitalization, the interior of the capital "U". Got it?

Okay! But what about the so-called " flutter", often confused with "fluttering", how often is it allowed to "flutter" harmoniously?

The tip: Rausatz is a highly "dangerous" combination and requires a lot of patience. And: it causes unpleasant separations. An additional difficulty! Let's move on to the inevitable separations: Every word is a term! So - if - then only in the syllable component. Avoid hyphenating short sentences such as "Hil-fe", which have to be "accommodated" either in the previous line or in the next. Nothing helps! Think about the language, hyphenation means stuttering when spoken! I used to say to my students, why don't you read out what you've "typographed" here ... and they would stutter. Typography is abstract language!

And now, finally, the "fringes" in the out set - how long or short can they be? The same principle as for the indent: the interplay of a minimum of 3 thick "M" - maximum 4! Anything that protrudes beyond this is like a branch that needs to be sawn off.

Realization: It is the letter in an alphabet that determines the indentation or the end of a line (which is individual, so be careful) It is always about the thick M or W, or the small u or n in the word spacing. Everything else is rubbish.

At the Bauersche Giesserei we had our own proofreader, a little man from a Fritz Lang movie, who mercilessly marked all mistakes with red, we feared him, but there was no mercy.

These are/were immutable rules. They applied in a time that was lost from the mid-seventies onwards. A legacy for my "young" future generations. Print it out. Hang it over your desk. On your super PC. Because there are things that endure and prove true.